- Home

- Reginald A Ray

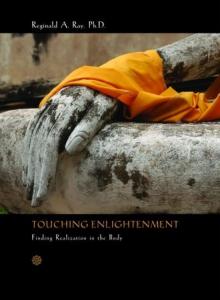

Touching Enlightenment

Touching Enlightenment Read online

TOUCHING ENLIGHTENMENT

Finding Realization in the body

Reginald A. Ray, Ph.D.

Table of Contents

ALSO BY REGINALD A. RAY

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Preface

INTRODUCTION

ONE:Touching Enlightenment with the Body

TWO:What Has Become of the Buddha’s Dharma?

THREE:The call of the Forest

FOUR:The Ultimate Challenge of Buddhism

I:OUR SOMATIC DISEMBODIMENT

FIVE:Modern Buddhism and Global Crisis

SIX:Our Physical Divestment

SEVEN:Our Emotional Disconnection

EIGHT:Some Historical Roots of Our Modern Disembodiment

NINE:Meditating without the Body

TEN:The Somatic Challenge of Tibetan Yoga

II:ENGAGING THE PROCESS: MEDITATING WITH THE BODY

ELEVEN:The Call to Return

TWELVE:How Do We Proceed?

THIRTEEN:Entering the Gate

FOURTEEN:Discomfort in the Somatic Practice

FIFTEEN:The Background and Process of Discomfort

SIXTEEN:The Process of Letting Go

SEVENTEEN:The Unfolding Journey

EIGHTEEN:The Body’s Own Agenda

III:UNDERSTANDING THE PROCESS OF MEDITATING WITH THE BODY

NINETEEN:The Importance o f Non-conceptual Understanding in the Body Work and Where Concepts Are Needed

TWENTY:What the Body Knows

TWENTY-ONE:What Happens to What Is Rejected?

TWENTY-TWO:An Example

TWENTY-THREE:Karma of Cause, Karma of Result

TWENTY-FOUR:Our Unlived Life

TWENTY-FIVE:The Body and Its Dimensions: The Full Extent of the Karma of Result

TWENTY-SIX:The Moment of Greatest Alienation

TWENTY-SEVEN:Beyond the Reactivity of Ego

TWENTY-EIGHT:Empowerment

TWENTY-NINE:Impersonal and Individual

THIRTY:The “Good News” of Chaos

THIRTY-ONE:The Body of the Buddha

IV:DYNAMICS OF THE PATH: PRINCIPLES, PRACTICES, AND EXPERIENCES

THIRTY-TWO:Developing Peace: Somatic Shamatha

THIRTY-THREE:Are We Willing to See? Somatic Vipashyana

THIRTY-FOUR:Falling Apart

THIRTY-FIVE:Tracking Our Emotions

THIRTY-SIX:Trusting Our Emotions

THIRTY-SEVEN:Imagination in the Body Work

THIRTY-EIGHT:A Tibetan Yoga Approach to Physical Pain

THIRTY-NINE:Some Fundamental Shifts

V:THE BODY AND BECOMING A PERSON

FORTY:The Body Is the Buddha Nature

FORTY-ONE:The Journey Is Our Unfolding Relation with the Buddha Nature

FORTY-TWO:Ego, the Body, and the Journey

FORTY-THREE:The First Stages of the Journey

FORTY-FOUR:Aspects of the Unfolding Process

FORTY-FIVE:A Tibetan View of the Major Stages of Unfolding

FORTY-SIX:The Body as Guide on the Journey

FORTY-SEVEN:Encountering the Shadow

FORTY-EIGHT:The Personal Body

FORTY-NINE:The Next Layer: The Interpersonal Body

FIFTY:Layers of the Interpersonal Body

FIFTY-ONE:How Other People Help Us Meet Our Shadow

FIFTY-TWO:Integrating Further Depths of the Shadow

FIFTY-THREE:The Cosmic Body I: Transcending the Scientific Worldview

FIFTY-FOUR:The Cosmic Body II: The Earth as Our Body

FIFTY-FIVE:The Cosmic Body III: The Initiatory Process

FIFTY-SIX:The Cosmic Body IV: Until the Very End of Being

FIFTY-SEVEN:Who Am I?

CONCLUSION

FIFTY-EIGHT:Becoming Who We Are

A Glimpse of the Body Work

Front Cover Flap

Back Cover Flap

Back Cover Material

Index

ALSO BY REGINALD A. RAY

BOOKS

Buddhist Saints in India: A Study in Buddhist Values and Orientations

Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism

Secret of the Vajra World: The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet

In the Presence of Masters: Wisdom from 30 Contemporary Tibetan Buddhist Teachers

The Pocket Tibetan Buddhism Reader

AUDIO

Buddhist Tantra: Teachings and Practices for Touching Enlightenment with the Body

Meditating with the Body: Six Tibetan Buddhist Meditations for Touching Enlightenment with the Body

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Charlotte B. MacJannet, an early and most important spiritual mentor, whom I met when I was barely eighteen and working in Europe. With remarkable prescience, “Mrs. Mac” initiated me into many of the core themes of my subsequent life and work. She gave me my first book on Tibetan Buddhism. She also introduced me to Jung, by arranging for me to meet and work briefly with one of Jung’s own students. And one day she said to me out of the blue, “You need to see the world; you need to see Asia.” Never one to speak idly, once I had signed on to this idea, she dug in and organized people for me to meet, work to do, and families to stay with during a year sojourn, from Japan, through Southeast Asia, to India, and then into Nepal, a journey that changed my life forever. Especially noteworthy in the present context, Mrs. Mac arranged for me to study with one of the students of Gerda Alexander, the Danish founder of Eutonie, a somatic discipline of much power and depth. Mrs. MacJannet’s deep optimism about the spiritual possibilities of modern people, her commitment to relieve suffering wherever she found it, and her joy in living were priceless gifts to all who knew her. Charlotte MacJannet passed away many years ago, before I was able to realize the tremendous debt I owe her and before I could adequately thank her for her great and selfless offerings at this critical moment in my life. Belatedly, then, Mrs. Mac, wherever you may be, I send you my devotion, my gratitude, and my love.

Acknowledgments

This book owes a great debt to many people, stretching back to my youth.

I must thank my academic teachers, especially H. Ganse Little, Bill Peck, Mircea Eliade, Charles Long, Joe Kitagawa, and Frank Reynolds, for providing me the training and the tools to explore Buddhist history to great depth. When I studied with them, I never could have imagined how important and useful that education would be, not only in my scholarly life, but also and even more so in my work as a dharma teacher attempting to teach meditation—and particularly the embodied meditation discussed in this book—in the modern world.

I thank my Buddhist teachers, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, H.H. Khyentse Rinpoche, H.H. the Sixteenth Karmapa, and the many other generous and gracious Tibetan lamas I have been privileged to learn from; Eido Roshi, Kobun Chino Roshi, and my other Zen mentors; and several wonderful Theravadin teachers who, in person and through their books, have taught me a great deal about meditating with the body. Thanks also to the indigenous men and woman who have showed me the universality of human spirituality and its groundedness in the earth and the body—and most of all to my heart-friend, the extraordinarily gifted African spiritual teacher Malidoma Patrice Somé. In addition, thanks to the many others I am happy to count as spiritual friends from the native traditions of both North and South America.

I have been exploring and studying somatic disciplines—both Western and Eastern—for my entire adult life, beginning with the work of Gerda Alexander. In subsequent years and down to the present, I have been most fortunate to have met and worked with a succession of gifted people representing Western traditions including various message modalities, Rolfing, and Feldenkreis and, from Asia, yoga, Qi Gong, and, of course, most significantly, Tibetan

yoga. All of this has been bound together by the transformative energy work of my wife, Lee, which has led me ever more deeply into my body and its inner health, wisdom, and perfection. My somatic learning over the past forty-five years has been very gradual, but it has changed my life. This book attempts to express something of how that has been so and what I have come to.

I owe a particular debt of gratitude to Tami Simon, publisher of Sounds True, and Julie Kramer, founder of Transmissions Creating Learning Lineages, who first encouraged me to begin teaching the “body work” as a discrete set of meditation instructions and who produced the intensive Meditating with the Body residential and at-home program that has, by now, led hundreds of people into the unfolding journey of somatic practice.

In immediate relation to Touching Enlightenment, I must thank Andrew Merz, editor at Tricycle magazine, who invited me to write the article upon which this book is based. Thanks also to those who read early drafts and provided some very useful perspectives and suggestions—in particular Sari Simchoni, Al Blum, John Welwood, and my wife, Lee, who read the manuscript at several crucial stages.

I offer much thanks, again, to Tami Simon, who invited me to publish Touching Enlightenment through Sounds True and provided a level of attention, commitment, and editorial skill beyond anything I have yet experienced in my previous publishing experience. Thanks especially to my Sounds True editors: my main editor Kelly Notaras, who worked on the manuscript with me with intelligence and energy throughout, and Andrew Merz, who did a second, most helpful editing of the manuscript.

Preface

To be awake, to be enlightened, is to be fully and completely embodied. To be fully embodied means to be at one with who we are, in every respect, including our physical being, our emotions, and the totality of our karmic situation. It is to be entirely present to who we are and to the journey of our own becoming. It is to inhabit, completely, our relative reality, with no speck of ourselves left over, no external observer waiting for something else or something better. In this sense, this book explores what it might mean to be fully embodied and, as such, what it might mean to be an enlightened or completely realized being, for they are one and the same.

What is presented here is an expression of the lineage of the Buddha. At the same time, it also has much in common both with depth psychology and with the various somatic methods and disciplines. But there are some important differences. While this book is an expression of the buddha-dharma, at least in relation to how that is often understood in the West, it is more somatically oriented. While my approach shares with some depth psychology and with transpersonal psychology an interest in the unfolding of the human personality as an ultimately spiritual matter, again, its methods tend more toward the body. In addition, it provides a path to fully individuated being that is available to anyone, not restricted to those who can afford long and costly psychotherapeutic work. And while this book shares ground with the various somatic schools and disciplines, it places much more emphasis on the “view” stressing that, simply in order to hear and integrate what arises in working with the body—in effect what the body is saying—a clear and accurate conceptual understanding of the subtle processes involved is necessary so we have the apparatus to receive, comprehend, and give voice to our experience.

As the reader will see, I draw deeply on Tibetan yoga, the corpus of esoteric, somatically based Buddhist meditation practices known in Tibet as tantra or Vajrayana, (the “Diamond Vehicle”), traditionally carried out primarily in solitary retreat. These I learned and have practiced for nearly forty years under the great teacher, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and other lamas in the Nyingma and Kagyu lineages. Also nourishing and deepening my understanding of the body as a spiritual reality has been the exploration of several Western modalities (the Alexander technique, Rolfing), fruitful studies with several Zen teachers, and contact with the Theravadin tradition. Also of great importance has been study and practice within several of the major “earth-based spiritualities” of the indigenous world. These include the native traditions of both North and South America and, most impactfully, several years of intensive work with my friend and heart brother Malidoma Somé, the gifted African spiritual teacher. Of particular impact in my study with Malidoma was an all-night “earth burial,” which, through its initiatory death and rebirth process, allowed my life to crumble and then arise in a way that established the earth and the “body work,” once and for all, as the core of my spiritual life. My experience with Malidoma also made it absolutely clear that tantra, or the Vajrayana, is, in essence, also an “earth-based spirituality,” though one surviving—sometimes in disguise—within a “high” religion, namely Buddhism.

Although this is not a book about practice—most of what I talk about here needs to be learned directly and in person from a qualified teacher—I do express many of the perspectives and insights of Tibetan yoga. It might be asked whether it is appropriate to be reflecting in print in this way on a tradition that has, in the past, been surrounded with much mystery and secrecy. My response is that the secrets and mysteries of Tibetan yoga are nothing other than the secrets of the human heart and the mysteries of human existence. As Thrangu Rinpoche once said in another context, surely it cannot be wrong to encourage people, however we may do so, to meet their uttermost depths, their ultimate self.

The work discussed in this book comprises a general approach to meditation and also a corpus of what I call “somatic protocols,” meditative practices that entail approaching, entering, exploring, and fully fathoming the body. Simply put, these practices involve extending awareness from the surface of the body into its interior, extending into its uttermost ground, from its larger parts down, perhaps, to a cellular level. Central to my teaching also is use of the breath, to open the body, to carry awareness to otherwise inaccessible levels of subtlety, and to unlock the inner energy and, hence, what Zen calls the “authentic life” of the practitioner that is waiting to be lived. I want to suggest that, through this process of “the body work” or “meditating with the body,” one’s basic experience, not just of one’s body, but of one’s very self, of one’s relation to others and to the natural world, opens in an unending series of discoveries and transformations. Though at first it may sound simple enough to talk about “meditating with the body,” in the end I think we may find that the work eventually brings us to a new understanding and, more important, a new experience of what it means to be human and what it means to be at all.

I offer this as an interim report, rather than as anything definitive. It is the account of what I and my students have been doing, experiencing, and thinking in relation to the somatic meditation and body explorations that I have been teaching to meditators and would-be meditators for many years now. If the reader notices a certain lack of finality in my presentation, I would respond that this is somewhat deliberate and, in fact, I have tried to resist the temptation to tidy my report up too much. What I am writing about here has its own life and its own reality transcending the limits of my own experience and surpassing any attempt to talk about it. In what follows, I have tried to respect that.

One cannot really write about spirituality. Of course, one can write about it, but in that case it is inevitably converted into a mere conceptual facsimile. In reading about spirituality today, it is all too common for people to confuse second-order concepts about spirituality with the primary, first-order experience of the spiritual life itself, to which no thought can be adequate. Thinking then becomes a substitute for the life itself, something that is both misleading and harmful. Lecturing about spirituality is better than writing about it—the human person of the lecturer—one hopes—stands closer to the actual locus of spirituality than does the printed page. Mentor talking with student one-on-one is better than lecturing—because the spiritual journey is ultimately individual. And the singular soul meditating in solitude is better than any talking, because it is only in the depths of individual experience that the spiritual can be discovered and

lived in a fully real way. Let me acknowledge, then, that writing about spirituality, as I have done here, is questionable at best. A lot of things have been tried over the past century to bring Asian Buddhism—and other non-Western forms of spirituality—to the West, and many have not worked. Attempting to write about the innermost integrity of the human person, as I have done here, may be one of them. Let the reader keep this in mind and make his or her own assessment.

—Reginald A. Ray

Crestone, Colorado

July, 2007

INTRODUCTION

ONE: Touching Enlightenment with the Body

Many years ago, while engaged in research for my book Buddhist Saints in India,1 I ran across a phrase—“touching enlightenment with the body”—that instantly captured my imagination and subsequently became a prolonged contemplation extending over at least two decades. Later, unsuccessfully, I tried to determine where I had first seen these words: Was it in a Pali text? Was it in a translation or commentary from the Theravadin tradition? Did I find it in a Mahayana or Vajrayana meditation manual? Or, perhaps, did I simply dream it or make it up?

Be that as it may, “touching enlightenment with the body” has defined my meditative life for a long time. What I still find so compelling is its suggestion that we are not to see enlightenment, but to touch it, and, further, that we are to touch it not with our thought or our mind, but with our body. It is interesting that this phrase of mysterious origin has many analogues within the Theravadin tradition itself: enlightenment, for humans, is frequently presented as a somatic experience. Dogen, the founder of the Japanese Soto School of Zen, sometimes spoke of the body as the gateway to ultimate realization, and the Dzogchen teachings of Tibet affirm that enlightenment is found in the body.

Touching Enlightenment

Touching Enlightenment